Trek to Death Valley

Posted on 26 December, 2023 / 2 min readVisiting Death Valley National Park is an experience unlike any other. Beneath the superficial dearth of vegetation and life hides an untold story of human struggle, ongoing evolution, and geologic change.

Since Ancient Times

Once deep under the Pacific Ocean, Death Valley is home to immense mineral salt deposits that, in addition to its extreme aridity, prevent most plants and animals from calling this area of the Mojave their home.

During my trip I had the rare opportunity to visit Death Valley's recently spawned salt lake, a rare phenomenon created from Hurricane Hilary's rains this past year that occurs approximately once in a thousand years.

Already a heavily trafficked tourist magnet, the lake also appears to have led to the unfortunate demise of numerous thirsty insects caught off-guard by the water's overwhelming salinity.

Curious as to lake's true degree of saltiness, my brother and I had the privilege of dipping our hands into a puddle and tasting some of the snow-like structures we stumbled across.

The water on our hands quickly evaporated into the arid air leaving behind a thick, crusty layer of salt that clung to our skin so strongly that our fingers' range of motion became very restricted.

Needless to say, the salt was saltier than any palatable substance, and elicited an understandable fit of spitting and coughing from those brave enough to taste it.

However, while the Badwater Basin Lake truly did seem devoid of any life beyond us homo sapiens tourists, I found Death Valley as a whole to be a menagerie of unique desert life, which I shall proceed to document for the interested reader.

Flourishing Life in Death Valley

One of the first things one notices when entering this nigh-Martian landscape is that the ground is littered with seemingly infinitely many small rocks.

With this as the pervasive ground-cover, it was not surprising that I was not able to find any trees during my short visit (although we saw a few Joshua Trees on the way there).

Nonetheless, in many areas certain shrubs, overwhelmingly grey-ish brown in color, decorate the otherwise endless sea of rocks and cleft ridges that a keen observer would correctly identify as the backdrop used in Star Wars scenes on Tatooine.

Firstly, the spiny Nevada ephedra.

This shrubbery was perhaps the most common plant we saw, and its dusty hue might trick an unacquainted eye to mistake it for some sort of dead tumbleweed.

Next, the purple-flowered Redstem stork's bill.

This invasive European species is extremely hardy in the harsh, sunny desert biomes across the world, surviving just fine even with Death Valley's highly variable temperature range between summer and winter. Unfortunately, it has contributed to the demise of California's native perennial grass species.

Then, the beautiful desert globe mallow.

This native species is just as drought tolerant as all the other residents of Death Valley. Flowering in winter like many of the plants we encountered, it blended in well with the mostly red-orange rocks it sprouted next to.

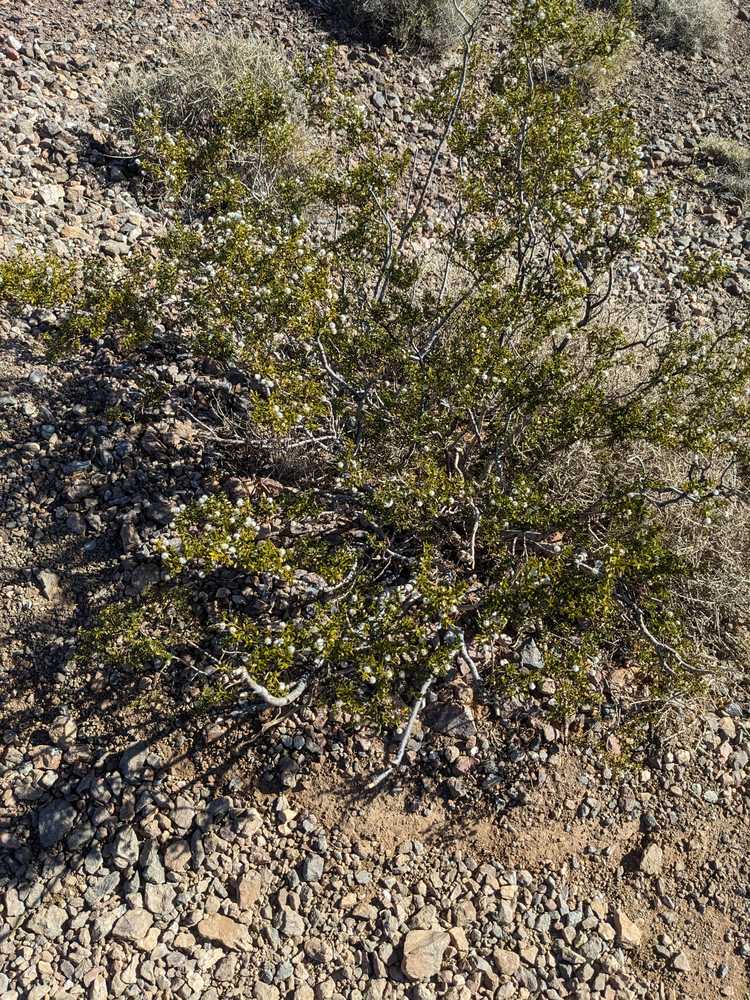

Last but not least, the creosote bush.

Reminiscent of a juniper though much more desert-hardy, this bush was perhaps the greenest organism we encountered in our entire trip. Its tiny evergreen leaves are said to smell like creosote, and it produces yellow flowers in spring and summer.

Needless to say, we encountered many more life forms beyond these four, including a baby tarantula trying to cross the road, a singular bird, and a few other plants I wasn't able to snapshot. Our tour guide said he even saw a bighorn sheep once in his 5 years of business as well as a few lizards and snakes during the summer (though apparently never a road-runner).

I highly recommend visiting this place, it is a land where many different paths have crossed and will likely continue to be in the future.

Tip: try to avoid getting your shoes salty because they will become hard to clean.